Rust’s Borrow Checker: How It Prevents Memory Bugs (and Where You Still Need to Be Careful)

The borrow checker was the most confusing thing I encountered as a Rust beginner coming from C++. It looked like a compiler plus linter at first, but I was wrong. Here I explore how to understand and use it to grasp Rust’s design philosophy

- Getting Past the Initial Frustration

- What the Borrow Checker Actually Prevents

- What C++ Hides, Rust Reveals

- Reading Errors as Design Feedback

- Decision Tree

- Common Patterns

- When You Need to Break the Rules

- What This Means for C++ Developers

- Summary

- Quick Reference

- References

Getting Past the Initial Frustration

The borrow checker frustrated me at first. After a long night of refactoring, I realized: the compiler wasn’t blocking my code—it was exposing design problems early.

Three things that changed my perspective:

tip Errors are hints, not blockers. The compiler points at fixable design issues.

- warning If the compiler complains, it’s usually protecting you: two parts of your code are trying to change the same data at the same time. Fix it by:

- Choose a single place that mutates the data.

- Split independent fields so each function only needs what it uses.

Queue changes and apply them later (event queue).

- important Only use

RefCellorRcwhen you really need them—not as a quick fix.

What the Borrow Checker Actually Prevents

✅ What Rust Prevents: Memory corruption, data races, use-after-free, iterator invalidation

⚠️ What It Doesn’t: Logic bugs, deadlocks, memory leaks (with Rc cycles), panics

🎯 Why It Matters: Eliminates the most dangerous 70% of bugs, forces architectural clarity

✅ What Rust PREVENTS

- Use-After-Free - Accessing freed memory

- Double-Free - Freeing memory twice

- Dangling Pointers - References to deallocated memory

- Data Races - Concurrent unsynchronized access

- Iterator Invalidation - Modifying while iterating

- Aliased Mutation - Multiple mutable access to same data

Example of what Rust catches:

// C++: Compiles, crashes later

std::vector<int> vec = {1, 2, 3};

int* ptr = &vec[0];

vec.push_back(4); // Reallocates!

*ptr = 10; // ❌ Dangling pointer - UB

// Rust: Rejected at compile time

let mut vec = vec![1, 2, 3];

let ptr = &vec[0];

vec.push(4); // ❌ ERROR: cannot borrow as mutable

*ptr = 10; // while borrowed immutably

⚠️ What Rust DOESN’T Prevent

- Logic Bugs - Wrong algorithms, off-by-one errors

- Deadlocks - Thread synchronization issues

- Memory Leaks - With Rc cycles

- Integer Overflow - In release mode

- Panics - Runtime errors from unwrap(), division by zero

- Resource Exhaustion - Running out of memory/handles

Examples that still compile but can be wrong:

// ✅ Compiles fine, but logic bug

fn calculate_average(numbers: &[i32]) -> i32 {

numbers.iter().sum::<i32>() / numbers.len() as i32

// Panics if numbers is empty!

}

// ✅ Compiles fine, but deadlock possible

let mutex1 = Arc::new(Mutex::new(1));

let mutex2 = Arc::new(Mutex::new(2));

// Thread A: locks mutex1, then mutex2

// Thread B: locks mutex2, then mutex1

// = Classic deadlock (still possible in Rust!)

Why It Still Matters

The borrow checker eliminates a whole class of bugs that plague C/C++:

Microsoft and Google data shows ~70% of security vulnerabilities are memory safety issues. Rust eliminates these at compile time.

The borrow checker doesn’t prevent all bugs—it prevents the most dangerous ones. You still need tests, but you’re debugging logic, not memory corruption.

What C++ Hides, Rust Reveals

Aliased Mutation Bug

// C++: Compiles fine, breaks later

class GameWorld {

std::vector<Entity> entities;

PhysicsEngine physics;

public:

void update() {

physics.simulate(entities); // Mutates entities

for (auto& e : entities) { // Concurrent iteration

e.updateBehavior(entities); // Can modify vector!

}

}

};

What’s happening:

graph TD

A[update called] --> B[physics.simulate mutates entities]

A --> C[for loop iterates entities]

B --> D[Vector may reallocate]

C --> E[entity.updateBehavior mutates entities]

D --> F[Iterator invalidation!]

E --> F

style F fill:#ff6b6b,stroke:#c92a2a,color:#fff

style D fill:#ffe066,stroke:#f08c00

style E fill:#ffe066,stroke:#f08c00

Hidden problems:

- Iterator invalidation (vector reallocation)

- Order-dependent behavior

- Race conditions when threaded

- No clear ownership

Rust Makes It Clear

// Rust: Rejected immediately

impl GameWorld {

fn update(&mut self) {

self.physics.simulate(&mut self.entities);

for e in &mut self.entities {

e.update_behavior(&mut self.entities);

// ❌ ERROR: cannot borrow as mutable more than once

}

}

}

The real question:

flowchart TD

A[Borrow checker error] --> B{Who owns mutation<br/>of entities at this moment?}

B --> C[Physics engine?]

B --> D[Each entity?]

B --> E[Game loop?]

C --> F[They can't ALL own it!]

D --> F

E --> F

F --> G[Choose ONE clear owner]

G --> H[Options:<br/>1. Phase separation<br/>2. Event queue<br/>3. Copy small data<br/>4. Use indices]

style B fill:#ffe066,stroke:#f08c00

style F fill:#ff6b6b,stroke:#c92a2a,color:#fff

style G fill:#51cf66,stroke:#2f9e44

style H fill:#51cf66,stroke:#2f9e44

The compiler asks: “Who owns mutation at this moment?” This is an architectural decision C++ lets you skip.

Reading Errors as Design Feedback

Pattern 1: Split Borrows

Error:

cannot borrow `game_state` as mutable more than once

Meaning: Your data structure doesn’t match your access patterns.

Fix:

struct InputHandler {

mouse: MouseState,

keyboard: KeyboardState,

camera: Camera,

}

impl InputHandler {

fn process(&mut self) {

// This fails

// handle_mouse(&mut self.mouse, &mut self.camera);

// handle_keyboard(&mut self.keyboard, &mut self.camera);

// Destructure to show independence

let Self { mouse, keyboard, camera } = self;

handle_mouse(mouse, camera);

handle_keyboard(keyboard, camera); // OK!

}

}

mouseandkeyboarddon’t need the whole handler—only their specific data. The error revealed independence.

Pattern 2: Lifetime Contracts

Problem:

struct Tag<'a> {

label: &'a str,

}

fn make_tag() -> Tag<'_> {

let s = String::from("session-42");

Tag { label: &s }

// ERROR: borrowed value does not live long enough

}

Memory diagram:

sequenceDiagram

participant Caller

participant make_tag

participant Stack

Caller->>make_tag: call make_tag()

activate make_tag

make_tag->>Stack: create String "session-42"

activate Stack

Note over Stack: String lives here<br/>on the stack

make_tag->>make_tag: create Tag { label: &s }

Note over make_tag: Tag references String

make_tag-->>Caller: return Tag

deactivate make_tag

destroy Stack

Note over Caller: DANGER: Tag references<br/>deallocated memory!<br/>Dangling pointer!

Solutions:

// Option 1: Own the data

struct Tag {

label: String,

}

fn make_tag() -> Tag {

Tag { label: String::from("session-42") }

}

// Option 2: Borrow from caller

fn make_tag<'a>(label: &'a str) -> Tag<'a> {

Tag { label } // Caller controls lifetime

}

Lifetimes are contracts. Who outlives whom? If you can’t answer, redesign.

Pattern 3: Interior Mutability

When it works:

// ✅ Caching: mutation is internal

use std::cell::OnceCell;

struct Image {

path: String,

bytes: OnceCell<Vec<u8>>, // Lazy load

}

impl Image {

fn data(&self) -> &[u8] { // Note: &self, not &mut

self.bytes.get_or_init(|| load_from_disk(&self.path))

}

}

When it doesn’t:

// ❌ Observable mutation behind &self

impl Settings {

fn set_mode(&self, m: Mode) { // Looks const but isn't!

self.mode.borrow_mut().replace(m);

}

}

If callers can see the change, require

&mut self. Interior mutability is for internal details only.

Decision Tree

flowchart TD

A[Borrow checker error] --> B{Real aliasing risk?<br/>Two mutations at once}

B -->|Yes| C[Redesign:<br/>• Split state<br/>• Copy small data<br/>• Use indices/IDs<br/>• Event queue]

B -->|No| D{Mutation visible<br/>externally?}

D -->|Yes| E[Wrong abstraction:<br/>Require &mut self<br/>or refactor phases]

D -->|No| F[Interior mutability OK:<br/>RefCell, Cell, OnceCell]

F --> G{Truly shared<br/>ownership?}

G -->|Yes| H[Use Rc/Arc:<br/>Read-mostly data<br/>Avoid Rc RefCell unless necessary]

G -->|No| I[Choose single owner:<br/>Pass refs or indices]

style C fill:#ff6b6b,stroke:#c92a2a,color:#fff

style E fill:#ff6b6b,stroke:#c92a2a,color:#fff

style F fill:#51cf66,stroke:#2f9e44

style H fill:#ffe066,stroke:#f08c00

style I fill:#51cf66,stroke:#2f9e44

Common Patterns

1. Copy Small Data

// Fighting borrows

fn spawn_projectile(&mut self, entity_id: EntityId) {

let entity = &self.entities[entity_id];

let proj = Projectile::new(entity.position);

self.projectiles.push(proj); // ERROR: already borrowed

}

// Copy what you need

fn spawn_projectile(&mut self, entity_id: EntityId) {

let position = self.entities[entity_id].position; // Copy

let proj = Projectile::new(position);

self.projectiles.push(proj); // OK!

}

Copying small data (12 bytes for Vec3) breaks the borrow dependency.

2. Use Indices, Not References

// Cross-references everywhere

struct Player<'a> {

weapon: &'a Weapon, // Lifetime hell

}

// Use handles

type WeaponId = usize;

struct Player {

weapon_id: WeaponId, // Just an index

}

struct GameWorld {

players: Vec<Player>,

weapons: Vec<Weapon>, // Central storage

}

impl GameWorld {

fn get_player_weapon(&self, player_id: usize) -> &Weapon {

let weapon_id = self.players[player_id].weapon_id;

&self.weapons[weapon_id]

}

}

Why this works:

- No lifetime constraints

- Easy to swap/modify

- Serialization is simple

- Clear ownership (store owns data)

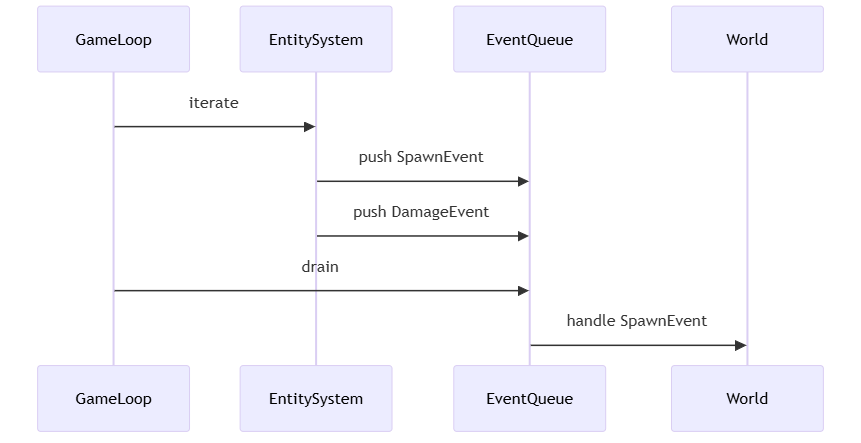

3. Event Queue Pattern

How it works:

The event queue pattern is used to avoid aliasing and borrowing issues by separating the decision phase (when you decide what needs to change) from the mutation phase (when you actually apply those changes). In a game engine, for example, entities and the main loop can push events (like spawning or damage) into a queue. The queue collects all events, and then the world processes them in a controlled, predictable order. This ensures that you never mutate data while iterating over it, and all changes happen in a single, well-defined phase.

The diagram below shows how different systems interact with the event queue:

- Entities: Push events (e.g., SpawnEvent, DamageEvent) into the queue.

- Loop: Drains the queue, triggering event handling.

- Queue: Holds all pending events.

- World: Handles each event, applying mutations.

flowchart TB

Entities -->|push SpawnEvent| Queue

Entities -->|push DamageEvent| Queue

Loop -->|drain| Queue

Queue -->|handle SpawnEvent| World

Queue -->|handle DamageEvent| World

// ✅ Defer mutations

fn update(&mut self) {

let mut events = Vec::new();

// Phase 1: Read-only iteration

for entity in &self.entities {

if entity.should_spawn() {

events.push(SpawnEvent {

position: entity.position,

// ...

});

}

}

// Phase 2: Apply mutations

for event in events {

self.handle_spawn(event);

}

}

Separate “read & decide” from “mutate & apply”. This is how game engines avoid aliasing issues.

When You Need to Break the Rules

RefCell: Runtime Borrow Checking

// Good: Internal caching

struct Metrics {

hits: RefCell<u64>,

}

impl Metrics {

fn hit(&self) {

*self.hits.borrow_mut() += 1;

}

}

// Bad: Hiding shared mutation

let config = Rc::new(RefCell::new(Config::default()));

module_a(config.clone()); // Who decides?

module_b(config.clone()); // Unclear!

Rc: Shared Ownership

// Good: Shared read-only data

let theme = Rc::new(Theme { color: "blue" });

let button = Button { theme: theme.clone() };

let label = Label { theme: theme.clone() };

// Bad: Shared mutation everywhere

let state = Rc::new(RefCell::new(State::default()));

// Now everyone can mutate—responsibility lost!

Breaking Reference Cycles

Pattern for tree structures:

graph TD

Parent[Parent Node<br/>Rc RefCell Node] -->|Rc owning| Child1[Child 1<br/>Rc RefCell Node]

Parent -->|Rc owning| Child2[Child 2<br/>Rc RefCell Node]

Child1 -.->|Weak non-owning| Parent

Child2 -.->|Weak non-owning| Parent

style Parent fill:#51cf66,stroke:#2f9e44

style Child1 fill:#74c0fc,stroke:#1971c2

style Child2 fill:#74c0fc,stroke:#1971c2

- Rc (Strong): Keeps data alive

- Weak: Doesn’t keep data alive, breaks cycles

- Parent owns children → when parent drops, children can be freed

- Children don’t own parent → no circular reference

What This Means for C++ Developers

These lessons transfer to any language:

- Make ownership explicit

// ❌ Unclear void setCallback(std::function<void()>* cb); // ✅ Clear ownership void setCallback(std::unique_ptr<std::function<void()>> cb); void setCallbackRef(std::function<void()>& cb); // Caller owns - Minimize shared mutable state

- Can one component be read-only?

- Can mutations be queued and batched?

- Question every

shared_ptr- Is this truly shared ownership?

- Or lazy design?

These questions matter in any language. Rust just forces you to answer upfront.

Summary

The borrow checker forces architectural clarity.

Questions it makes you ask:

- Who owns this data?

- When does mutation happen?

- What depends on what?

- Is this coupling intentional?

Impact:

graph TB

A[Level 1: Safety<br/>Eliminates 70% of bugs<br/>No use-after-free<br/>No data races] --> B[Level 2: Design<br/>Forces clear ownership<br/>Makes dependencies explicit<br/>Prevents hidden coupling]

B --> C[Level 3: Thinking<br/>Architectural mindset<br/>Questions assumptions<br/>Transferable to any language]

style A fill:#51cf66,stroke:#2f9e44

style B fill:#74c0fc,stroke:#1971c2

style C fill:#ffe066,stroke:#f08c00

When the compiler says “no,” it’s revealing a design clarity issue—not a language limitation.

Quick Reference

| Situation | Solution | Tool |

|---|---|---|

| Multiple mutable borrows | Split into independent fields | Destructuring |

| Need data from borrowed struct | Copy small values (IDs, positions) | Copy trait |

| Cross-struct references | Use indices/IDs instead | HashMap<ID, T> |

| Deferred mutations | Collect events, apply later | Vec<Event> |

| Internal caching | Interior mutability | Cell, OnceCell |

| Shared read-only data | Reference counting | Rc<T> |

| Tree with parent links | Break cycles | Rc + Weak |