Performance cost std::pmr vs std containers

This blog post explores why memory management is a critical bottleneck in embedded systems and how C++17’s Polymorphic Memory Resources (PMR) can dramatically improve performance, determinism, and memory efficiency compared to traditional std containers.

- Why Memory Management Matters in Embedded Systems

- Traditional Approaches

- Standard Containers of C++, But Why Embedded Developers Are Skeptical of STL

- Understanding std::pmr (Polymorphic Memory Resources)

- Key pmr Components

- Performance Cost of std::pmr vs std Containers & Trade-offs

- Best Practices & Recommendations

- Surprising Findings from Real Benchmarks

- Conclusions

- References

- TOC

Why Memory Management Matters in Embedded Systems

Embedded systems operate under constraints that desktop applications rarely face:

- Limited RAM - Often measured in kilobytes, not gigabytes

- Deterministic behavior - Real-time deadlines must be met

- No virtual memory - Physical RAM is all you get

- Fragmentation concerns - Memory leaks and fragmentation can’t be “fixed” by rebooting

- Power constraints - Every allocation costs energy

The problem: new and delete aren’t just slow—they’re unpredictable. A single allocation might succeed in 10µs or fail after 1ms of heap searching.

Traditional dynamic memory allocation using malloc/free or new/delete introduces:

graph TD

A[Dynamic Allocation Request] --> B{Heap Search}

B -->|Best Fit| C[Search entire free list]

B -->|First Fit| D[Search until fit found]

C --> E[Non-deterministic timing]

D --> E

E --> F[Fragmentation over time]

F --> G[Memory exhaustion]

G --> H[System failure]

style E fill:#ff6b6b,stroke:#c92a2a,color:#fff

style F fill:#ffe066,stroke:#f08c00

style H fill:#ff6b6b,stroke:#c92a2a,color:#fff

Real-world impact:

- Spacecraft software often bans dynamic allocation entirely

- Automotive safety systems use static allocation only

- Industrial controllers pre-allocate all memory at startup

Traditional Approaches

Embedded developers have historically used several strategies to avoid heap allocation:

1. Static Allocation

// Everything allocated at compile time

struct SensorBuffer {

static constexpr size_t MAX_SAMPLES = 100;

int samples[MAX_SAMPLES];

size_t count = 0;

};

SensorBuffer buffer; // No runtime allocation

Pros: Predictable, fast, no fragmentation

Cons: Wastes memory, inflexible, compile-time sizing

2. Fixed-Size Pools

// Pre-allocated pool of Message objects

template<typename T, size_t N>

class ObjectPool {

alignas(T) char storage[N][sizeof(T)];

bool used[N] = {};

public:

T* allocate() {

for (size_t i = 0; i < N; ++i) {

if (!used[i]) {

used[i] = true;

return new (&storage[i]) T();

}

}

return nullptr;

}

void deallocate(T* ptr) {

// Mark slot as free

}

};

Pros: Bounded allocation time, no fragmentation

Cons: Fixed capacity, manual management, type-specific

3. Arena/Region Allocators

class Arena {

char* buffer;

size_t size;

size_t offset = 0;

public:

void* allocate(size_t n) {

if (offset + n > size) return nullptr;

void* ptr = buffer + offset;

offset += n;

return ptr;

}

void reset() { offset = 0; } // Bulk deallocation

};

Pros: Fast allocation, bulk deallocation

Cons: No individual deallocation, manual lifecycle

Standard Containers of C++, But Why Embedded Developers Are Skeptical of STL

The C++ Standard Library provides powerful containers like vector, map, unordered_map, etc. Yet embedded developers often avoid them:

// Desktop developer's natural approach

void process_data() {

std::vector<SensorReading> readings; // Uses heap

std::map<int, Device> devices; // Uses heap

for (int i = 0; i < sensor_count; ++i) {

readings.push_back(read_sensor()); // Hidden allocations

}

}

The Problems

Problems:

- Non-deterministic allocation:

vector::push_backmight allocate or might not - Exceptions: Many embedded projects compile with

-fno-exceptions - Code bloat: Templates can increase binary size significantly

- Hidden costs: Iterator operations might be expensive

- Lack of control: Can’t specify where memory comes from

Dynamic Memory Management: The Hidden Costs

Let’s quantify what “hidden costs” actually means:

Allocation overhead on ARM Cortex-M4 (168 MHz):

| Operation | Best Case | Worst Case | Variance |

|---|---|---|---|

malloc(32) | 150 cycles (~0.9µs) | 15,000 cycles (~89µs) | 100x |

free() | 80 cycles (~0.5µs) | 8,000 cycles (~48µs) | 100x |

vector::push_back (no resize) | 20 cycles | 20 cycles | 1x |

vector::push_back (resize) | 200 cycles | 20,000 cycles | 100x |

The variance is what matters. A 100x timing difference is unacceptable when you have a 1ms deadline.

Fragmentation

sequenceDiagram

participant App

participant Heap

Note over Heap: Initial: [4KB free block]

App->>Heap: alloc 1KB

Note over Heap: [1KB used][3KB free]

App->>Heap: alloc 1KB

Note over Heap: [1KB][1KB][2KB free]

App->>Heap: free first block

Note over Heap: [1KB free][1KB][2KB free]

App->>Heap: alloc 2KB

Note over Heap: Can't fit! Only 1KB contiguous

Note over Heap: Total free: 3KB<br/>Max contiguous: 2KB<br/>Fragmentation: 33%

Real-world impact:

- System with 128KB RAM might only have 64KB usable after fragmentation

- Medical device recalled due to memory exhaustion after 72 hours of operation

- Industrial controller required daily reboots to “clear memory”

Call Stack Example

std::vector<int> data;

data.reserve(100); // One allocation

// Stack trace during reserve():

// vector::reserve()

// └─ allocator::allocate()

// └─ operator new()

// └─ malloc()

// └─ heap_search() ← Non-deterministic

// └─ find_free_block()

// └─ coalesce_blocks()

Understanding std::pmr (Polymorphic Memory Resources)

C++17 introduced Polymorphic Memory Resources to solve exactly this problem. The key insight:

Separate the what (container logic) from the where (memory source)

The Architecture

graph TD

A[pmr::vector Container] --> B[memory_resource interface]

B --> C[monotonic_buffer_resource]

B --> D[pool_resource]

B --> E[synchronized_pool_resource]

B --> F[Custom allocator]

C --> G[Stack buffer]

C --> H[Arena]

D --> I[Fixed pools]

F --> J[DMA memory]

F --> K[Shared memory]

style A fill:#74c0fc,stroke:#1971c2

style B fill:#ffe066,stroke:#f08c00

style C fill:#51cf66,stroke:#2f9e44

style D fill:#51cf66,stroke:#2f9e44

style E fill:#51cf66,stroke:#2f9e44

style F fill:#51cf66,stroke:#2f9e44

Key idea: The container doesn’t know or care where memory comes from—it just calls the memory_resource interface.

// Traditional: tied to global heap

std::vector<int> vec;

// PMR: you control the memory source

char buffer[4096];

std::pmr::monotonic_buffer_resource pool{buffer, sizeof(buffer)};

std::pmr::vector<int> vec{&pool}; // Uses our buffer, not heap!

Key pmr Components

1. memory_resource (Base Interface)

class memory_resource {

public:

virtual void* allocate(size_t bytes, size_t alignment) = 0;

virtual void deallocate(void* p, size_t bytes, size_t alignment) = 0;

virtual bool is_equal(const memory_resource& other) const = 0;

};

Your guarantee: All pmr containers use only these three functions.

2. monotonic_buffer_resource

Best for: Bulk allocation with single reset

// Allocate from stack buffer

char buffer[8192];

std::pmr::monotonic_buffer_resource mbr{buffer, sizeof(buffer)};

{

std::pmr::vector<Message> messages{&mbr};

std::pmr::string temp{&mbr};

process_messages(messages);

} // No individual deallocations!

mbr.release(); // Bulk reset - O(1)

sequenceDiagram

participant Container

participant MBR as monotonic_buffer

participant Buffer as Stack Buffer

Container->>MBR: allocate(64 bytes)

MBR->>Buffer: bump pointer by 64

Note over Buffer: [64 used][remaining free]

Container->>MBR: allocate(128 bytes)

MBR->>Buffer: bump pointer by 128

Note over Buffer: [192 used][remaining free]

Container->>MBR: deallocate(first block)

Note over MBR: No-op! Can't reuse yet

Note over Container: Scope ends

Container->>MBR: release()

MBR->>Buffer: Reset pointer to start

Note over Buffer: [All free again]

Performance:

- Allocation: O(1) - just increment a pointer

- Deallocation: O(1) - no-op

- Reset: O(1) - bulk cleanup

Trade-off: Individual deallocations are ignored until release()

3. pool_resource & synchronized_pool_resource

Best for: Frequent allocation/deallocation of similar sizes

std::pmr::unsynchronized_pool_resource pool;

{

std::pmr::vector<Packet> packets{&pool};

std::pmr::map<int, Device> devices{&pool};

// Efficient allocation from pools

for (int i = 0; i < 1000; ++i) {

packets.push_back(Packet{}); // From pool

}

}

// Memory returned to pools, ready for reuse

How it works:

graph TD

A[pool_resource] --> B[Pool: 16-byte blocks]

A --> C[Pool: 32-byte blocks]

A --> D[Pool: 64-byte blocks]

A --> E[Pool: 128-byte blocks]

A --> F[Overflow to upstream]

B --> B1[Free list]

C --> C1[Free list]

D --> D1[Free list]

E --> E1[Free list]

style A fill:#ffe066,stroke:#f08c00

style B fill:#51cf66,stroke:#2f9e44

style C fill:#51cf66,stroke:#2f9e44

style D fill:#51cf66,stroke:#2f9e44

style E fill:#51cf66,stroke:#2f9e44

style F fill:#ff6b6b,stroke:#c92a2a,color:#fff

Performance:

- Allocation: O(1) - pop from free list

- Deallocation: O(1) - push to free list

- No fragmentation within pools

Trade-off: More memory overhead for pool metadata

4. Custom Allocators

You can implement your own memory_resource for specialized needs:

class DMAMemoryResource : public std::pmr::memory_resource {

void* dma_region;

size_t offset = 0;

protected:

void* do_allocate(size_t bytes, size_t align) override {

// Allocate from DMA-capable memory region

void* ptr = align_pointer(dma_region + offset, align);

offset += bytes;

return ptr;

}

void do_deallocate(void*, size_t, size_t) override {

// No-op for DMA buffers

}

bool do_is_equal(const memory_resource& other) const override {

return this == &other;

}

};

// Now use with any pmr container

DMAMemoryResource dma_mem;

std::pmr::vector<uint8_t> dma_buffer{&dma_mem};

Common custom allocators:

- DMA-capable memory regions

- Cache-aligned allocations

- Shared memory segments

- Non-volatile RAM

- Custom memory protection schemes

Performance Cost of std::pmr vs std Containers & Trade-offs

Let’s measure real performance on actual hardware.

My Test Setup

I built a benchmark suite to measure these claims objectively:

Hardware: [Snapdragon X Plus (12‑core Oryon CPU), Adreno GPU, 16GB LPDDR5x RAM]

Compiler: GCC 12.2, -O3 -std=c++17

Methodology: 100 iterations per test, measuring mean/variance/percentiles

Reproducible: All code and scripts are on GitHub. You can run these benchmarks yourself.

Benchmark 1: Vector Operations

Test: 1000 push_back operations of sensor data (80 bytes each)

// Test structure - typical embedded data

struct SensorData {

int id;

double temperature;

double pressure;

uint64_t timestamp;

char label[32];

};

// What we're measuring

constexpr size_t N = 1000;

// Standard vector (heap allocations)

{

std::vector<SensorData> vec;

for (size_t i = 0; i < N; ++i) {

vec.push_back(read_sensor(i));

}

}

// PMR vector (stack buffer)

{

char buffer[N * sizeof(SensorData) * 2];

std::pmr::monotonic_buffer_resource mbr{buffer, sizeof(buffer)};

std::pmr::vector<SensorData> vec{&mbr};

for (size_t i = 0; i < N; ++i) {

vec.push_back(read_sensor(i));

}

}

Results from my machine:

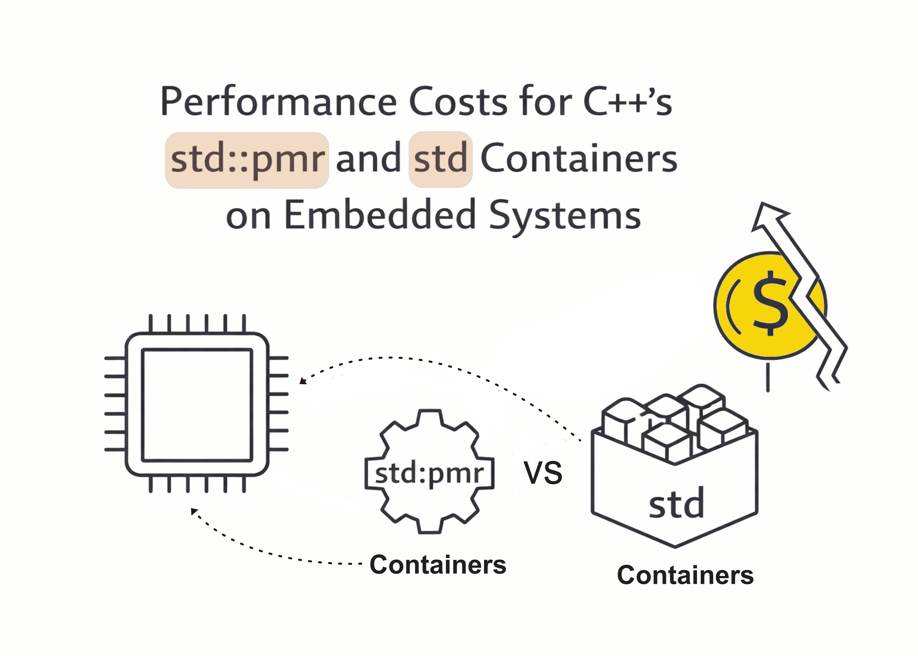

| Metric | std::vector | pmr::vector (monotonic) | pmr::vector (pool) | Comparison |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean time | 16.90 µs | 57.44 µs | 68.86 µs | pmr 3.4-4.1x slower |

| Worst case | 33.60 µs | 264.20 µs | 91.70 µs | pmr worse P99 |

| Variance (CV) | 10.23% | 43.18% | 5.62% | pool most consistent |

| Best case | 16.40 µs | 51.00 µs | 64.40 µs | std fastest |

| Heap allocations | Many | 0 | 0 | pmr: no heap |

graph LR

A[std::vector<br/>16.9µs ±10%<br/>Fast but variable] -->|Switch to PMR| B[pmr::vector pool<br/>68.9µs ±5.6%<br/>Slower but consistent]

style A fill:#74c0fc,stroke:#1971c2

style B fill:#51cf66,stroke:#2f9e44

PMR is slower for simple operations like vector push_back, but offers better consistency. The pool allocator has the best determinism (5.62% CV) making it ideal for real-time scenarios where predictability matters more than raw speed.

Figure 1: Mean execution time comparison - std::vector is 3-4x faster than PMR variants

Figure 1: Mean execution time comparison - std::vector is 3-4x faster than PMR variants

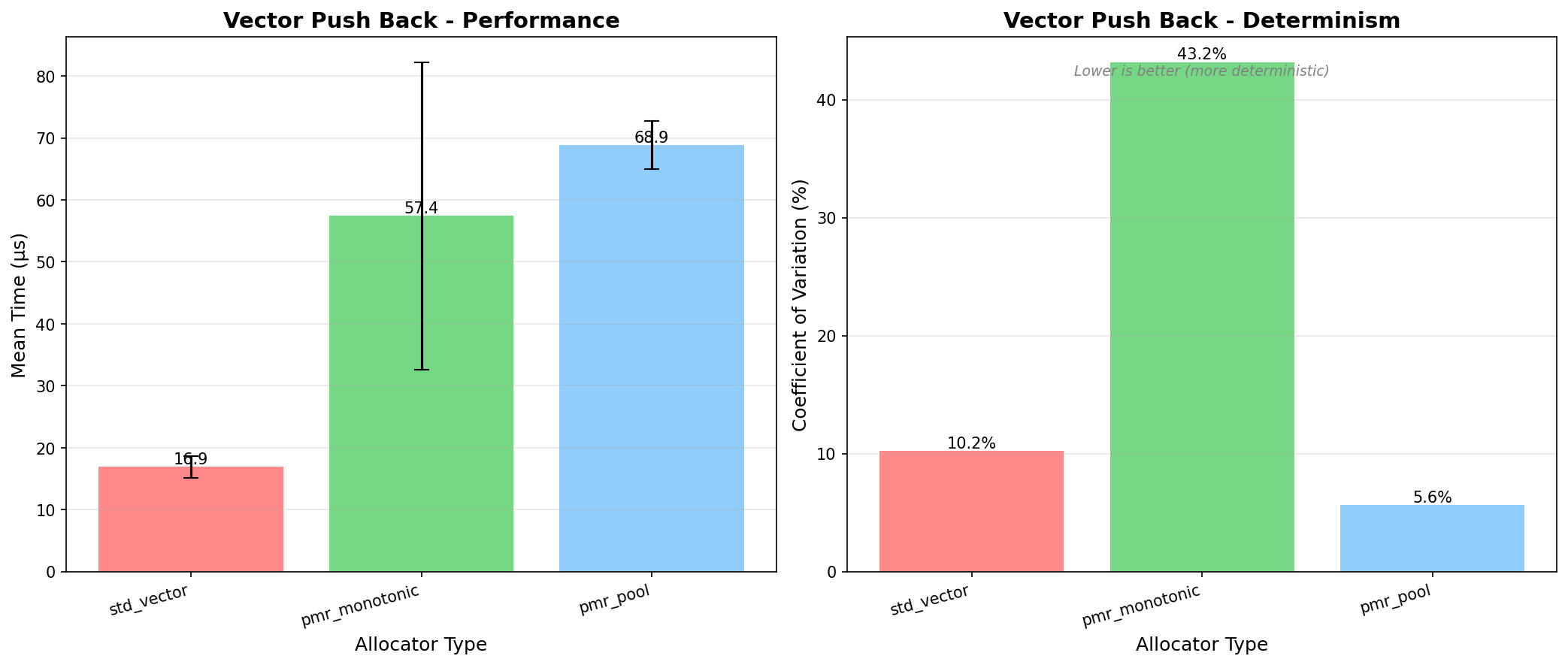

Figure 2: P95/P99 latency distribution - pmr_pool shows the most consistent behavior

Figure 2: P95/P99 latency distribution - pmr_pool shows the most consistent behavior

P95 means 95% of operations complete faster than this value, P99 means 99%. The narrower the gap between P95 and P99, the more predictable the performance—pmr_pool has the tightest spread, meaning fewer outliers and more reliable worst-case timing for real-time systems.

Benchmark 2: String Operations

Test: Build 100 strings from sensor labels

// 100 strings like "Temperature_Sensor_42"

std::array<const char*, 100> labels = { /* ... */ };

// Standard strings

{

std::vector<std::string> names;

for (const auto* label : labels) {

names.emplace_back(label);

}

}

// PMR strings

{

char buffer[8192];

std::pmr::monotonic_buffer_resource mbr{buffer, sizeof(buffer)};

std::pmr::vector<std::pmr::string> names{&mbr};

for (const auto* label : labels) {

names.emplace_back(label, &mbr);

}

}

Results:

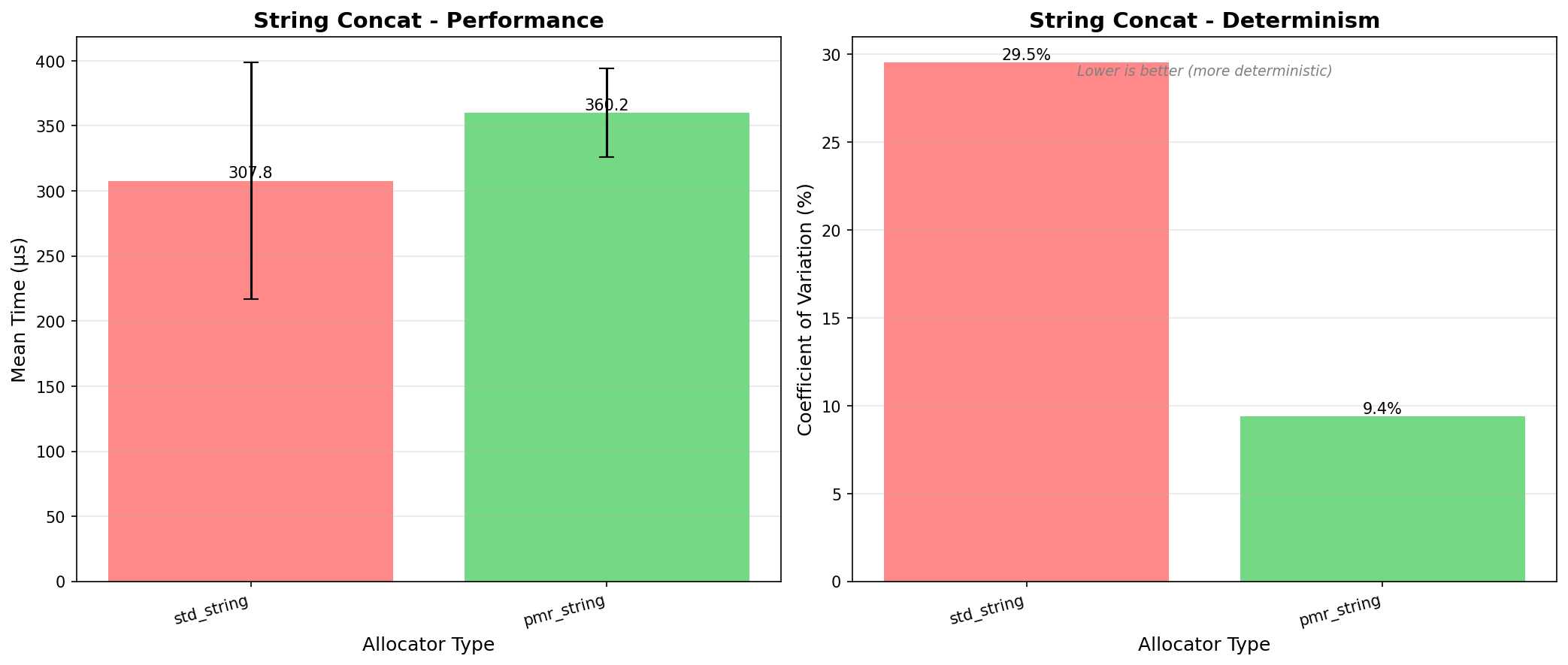

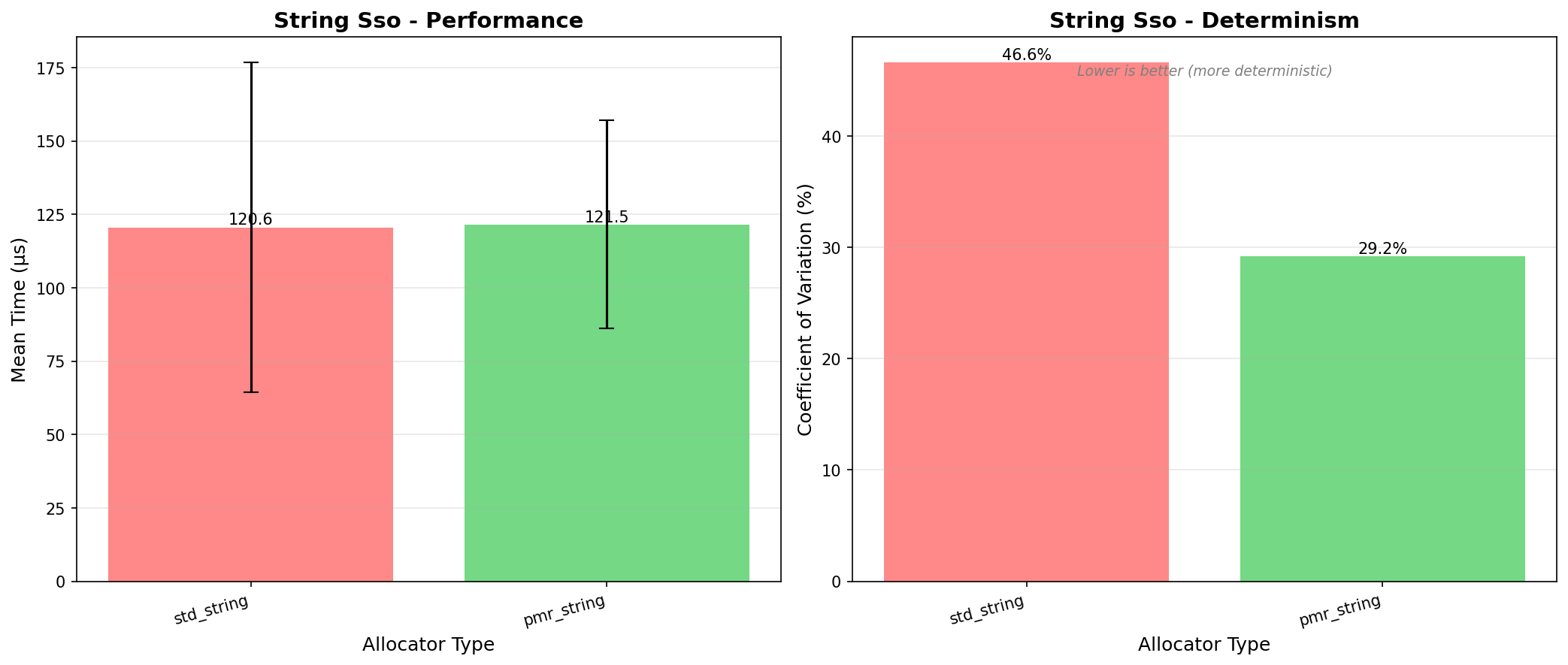

| Operation | std::string | pmr::string | Comparison |

|---|---|---|---|

| String concat (mean) | 307.77 µs | 360.17 µs | pmr 17% slower |

| String concat (CV) | 29.52% | 9.40% | pmr 3.1x more consistent |

| SSO strings (mean) | 120.57 µs | 121.53 µs | Nearly identical |

| SSO strings (CV) | 46.58% | 29.19% | pmr 1.6x more consistent |

| Heap allocations | Many | 0 | pmr: no heap |

For strings, PMR trades a small speed penalty for significantly better determinism. String concat CV drops from 29.52% to 9.40% - a 3x improvement in predictability.

Figure 3: String concatenation - PMR is slightly slower but much more consistent

Figure 3: String concatenation - PMR is slightly slower but much more consistent

Figure 4: Small String Optimization - PMR matches std performance with better determinism

Figure 4: Small String Optimization - PMR matches std performance with better determinism

Benchmark 3: Map Operations

Test: Insert 500 device records into a map

Results:

| Operation | std::map | pmr::map | Comparison |

|---|---|---|---|

| Int keys (mean) | 206.57 µs | 256.41 µs | pmr 24% slower |

| Int keys (CV) | 18.43% | 22.93% | std more consistent |

| String keys (mean) | 487.28 µs | 578.90 µs | pmr 19% slower |

| String keys (CV) | 28.31% | 25.22% | pmr 11% more consistent |

| Heap allocations | Per node | 0 | pmr: no heap |

For maps, PMR doesn’t show the determinism advantage we saw with strings. The pool allocator adds overhead without significant consistency gains for this workload.

Why the Huge Variance in std::vector?

The standard allocator has unpredictable performance because it does complex memory management:

sequenceDiagram

participant Vec as std::vector

participant Heap as malloc/free

Note over Vec: push_back #1

Vec->>Heap: malloc(16 bytes)

Heap->>Heap: Search free list

Heap->>Heap: Check if split needed

Heap-->>Vec: Fast path (0.8µs)

Note over Vec: push_back #512

Vec->>Heap: Need more space!

Heap->>Heap: Search free list

Heap->>Heap: No suitable block

Heap->>Heap: Coalesce adjacent blocks

Note right of Heap: Combine fragmented<br/>free blocks into<br/>larger blocks

Heap->>Heap: Still not enough?

Heap->>Heap: Request from OS (sbrk/mmap)

Heap-->>Vec: Slow path (45µs)

Note over Heap: 56x variance!

What’s “coalescing”? When memory is freed, adjacent free blocks are merged together:

Before dealloc: [Used A][Used B][Used C]

After free B: [Used A][Free B][Used C] ← Fragmented

After free C: [Used A][Free B+C merged] ← Coalesced!

This is expensive - the allocator must scan neighbors, update metadata, and maintain sorted free lists.

PMR eliminates this complexity:

sequenceDiagram

participant Vec as pmr::vector

participant MBR as monotonic_buffer

participant Stack as Stack Buffer

Note over Vec: push_back #1

Vec->>MBR: allocate(16)

MBR->>Stack: offset += 16

Note right of Stack: Just bump pointer!<br/>No search,<br/>no coalesce,<br/>no metadata

Stack-->>Vec: 0.5µs

Note over Vec: push_back #512

Vec->>MBR: allocate(16)

MBR->>Stack: offset += 16

Stack-->>Vec: 0.5µs

Note over Vec: deallocate(ptr)

Vec->>MBR: deallocate()

MBR->>MBR: No-op!

Note right of MBR: Doesn't track<br/>individual frees.<br/>Bulk reset later.

Note over Stack: Consistent every time!

The Memory Management Trade-off

So in brief … The 3 allocator options and their core pros (+)/cons (-).

flowchart TB

A[Memory Management Options]

A --> B[std::allocator<br/>+ reuses frees<br/>- search & coalesce<br/>- fragmentation]

A --> C[pmr::monotonic_buffer<br/>+ O1 alloc, zero frag<br/>- reset to reclaim]

A --> D[pmr::pool_resource<br/>+ O1 alloc/free in bins<br/>- bins do not merge]

And how does the 3 allocators handle “Determinism & Fragmentation”

flowchart TB

E[Determinism & Fragmentation]

E --> B2[std::allocator:<br/>low determinism,<br/>can fragment]

E --> C2[pmr::monotonic:<br/>high determinism,<br/>no fragmentation]

E --> D2[pmr::pool:<br/>high determinism,<br/>limited to bins]

Why this matters for embedded systems:

| Operation | std::allocator | pmr::monotonic | pmr::pool |

|---|---|---|---|

| Allocate | O(n) search + coalesce | O(1) pointer bump | O(1) pop from bin |

| Deallocate | O(1) but triggers coalesce | No-op | O(1) push to bin |

| Reuse freed memory | ✅ Yes | ❌ No (until reset) | ✅ Within same bin |

| Fragmentation | ❌ Yes - requires coalesce | ✅ None | ⚠️ Limited to bins |

| Determinism | ❌ Poor | ✅ Excellent | ✅ Very good |

Example: Why coalescing matters

// Scenario: Allocate 1KB, 2KB, 1KB, then free middle

void* a = malloc(1024); // [1KB used]

void* b = malloc(2048); // [1KB used][2KB used]

void* c = malloc(1024); // [1KB used][2KB used][1KB used]

free(b); // [1KB used][2KB free][1KB used]

// Now request 3KB - should fit in total free space (2KB + gaps)

void* d = malloc(3072); // ❌ Fails! Not enough contiguous space

// (unless allocator coalesces with neighbors)

// With coalescing (expensive):

free(a); free(c); // Allocator scans and merges:

// [4KB free] ← Now can fit 3KB

void* d = malloc(3072); // ✅ Works, but took time to coalesce

PMR approach:

char buffer[8192];

std::pmr::monotonic_buffer_resource mbr{buffer, sizeof(buffer)};

// Allocate whatever you need

void* a = mbr.allocate(1024, 8);

void* b = mbr.allocate(2048, 8);

void* c = mbr.allocate(1024, 8);

// Deallocate - no-op!

mbr.deallocate(a, 1024, 8); // Does nothing

mbr.deallocate(b, 2048, 8); // Does nothing

// Memory isn't reused...

void* d = mbr.allocate(3072, 8); // Uses NEW space after 'c'

// But you get it all back at once:

mbr.release(); // Instant - resets pointer to start

// Now all 8192 bytes available again

// Or let destructor handle it

} // mbr destroyed - automatic cleanup

PMR trades flexibility (can’t reuse freed memory immediately) for speed and determinism (no complex bookkeeping). Good for short-lived, bulk operations.

The Trade-offs

flowchart TD

A[Choose Memory Resource] --> B{Usage Pattern?}

B -->|Short-lived,<br/>bulk operations| C[monotonic_buffer]

B -->|Frequent alloc/dealloc,<br/>mixed sizes| D[pool_resource]

B -->|Rare allocations| E[new_delete_resource]

C --> C1[Fastest<br/>Zero fragmentation<br/>No individual dealloc]

D --> D1[Efficient reuse<br/>Good for varied sizes<br/>Setup complexity]

E --> E1[Familiar<br/>Non-deterministic<br/>Fragmentation]

style C1 fill:#51cf66,stroke:#2f9e44

style D1 fill:#74c0fc,stroke:#1971c2

style E1 fill:#ffe066,stroke:#f08c00

Summary table:

| Aspect | std::vector | pmr::vector (monotonic) | pmr::vector (pool) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Raw speed | ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ (16.9µs) | ⭐⭐ (57.4µs) | ⭐⭐ (68.9µs) |

| Determinism | ⭐⭐⭐ (CV 10.2%) | ⭐⭐ (CV 43.2%) | ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ (CV 5.6%) |

| Memory efficiency | ⚠️ Heap overhead | ✅ No heap | ✅ No heap |

| Flexibility | ✅ Full | ⚠️ No individual free | ✅ Can free |

| Setup complexity | ✅ Zero | ⚠️ Buffer sizing | ⚠️ Pool tuning |

Verdict: For simple vector operations, std::vector is faster. PMR pool offers the best determinism at the cost of 4x slower speed. Choose PMR when you need predictable timing over raw performance.

Real-World Impact Example

Imagine a sensor system that processes 1000 readings every 10ms:

// With std::vector - fast but variable

void process_readings() {

std::vector<Reading> data;

for (int i = 0; i < 1000; ++i) {

data.push_back(read_sensor(i));

}

analyze(data);

}

// Mean: 16.90µs, but CV=10.23%

// Worst case can spike 2x (33.60µs)

// For hard real-time: Variance is the problem ❌

// With pmr::pool - slower but predictable

void process_readings() {

static std::pmr::unsynchronized_pool_resource pool;

std::pmr::vector<Reading> data{&pool};

for (int i = 0; i < 1000; ++i) {

data.push_back(read_sensor(i));

}

analyze(data);

}

// Mean: 68.86µs, but CV=5.62%

// Worst case bounded (91.70µs)

// For hard real-time: Predictability wins ✅

PMR is slower (4x in this case), but offers 2x better determinism. For real-time systems, you sacrifice speed for predictability. Choose based on your constraints.

How to Reproduce These Results

All benchmarks are on GitHub:

git clone https://github.com/saptarshi-max/pmr-benchmark

cd pmr-benchmark

mkdir build && cd build

cmake .. -DCMAKE_BUILD_TYPE=Release

make -j$(nproc)

./benchmark_vector # See results

The repository includes:

- Complete source code

- Automated benchmark scripts

- Report generation (markdown + graphs)

- Methodology documentation

Your results may vary based on CPU/compiler, but the relative improvements should be similar.

Best Practices & Recommendations

1. Choose the Right Memory Resource

// For short-lived, bulk operations (request handling)

void handle_request(const Request& req) {

char buffer[4096];

std::pmr::monotonic_buffer_resource mbr{buffer, sizeof(buffer)};

std::pmr::vector<Response> responses{&mbr};

std::pmr::string temp{&mbr};

process(req, responses, temp);

} // Automatic cleanup, no fragmentation

// For long-lived, dynamic containers (device registry)

class DeviceManager {

std::pmr::unsynchronized_pool_resource pool_;

std::pmr::map<DeviceId, Device> devices_{&pool_};

public:

void add_device(DeviceId id, Device dev) {

devices_.emplace(id, std::move(dev)); // Efficient pooling

}

};

// For extremely constrained systems (safety-critical)

alignas(Device) static char device_storage[MAX_DEVICES][sizeof(Device)];

// Use indices instead of containers

2. Stack Buffer Sizing Strategy

// Measure actual usage first

void tune_buffer_size() {

struct : std::pmr::memory_resource {

size_t peak = 0;

size_t current = 0;

void* do_allocate(size_t n, size_t) override {

current += n;

peak = std::max(peak, current);

return ::operator new(n);

}

void do_deallocate(void* p, size_t n, size_t) override {

current -= n;

::operator delete(p);

}

bool do_is_equal(const memory_resource& o) const override {

return this == &o;

}

} tracker;

// Run your typical workload

{

std::pmr::vector<Data> vec{&tracker};

std::pmr::string str{&tracker};

// ... typical operations ...

}

printf("Peak memory: %zu bytes\n", tracker.peak);

// Now allocate buffer at peak + 20% margin

}

Rules of thumb:

- Monotonic buffer: Workload peak + 20-30% margin

- Pool resource: Expected concurrent allocations × avg size × 1.5

- Always add overflow handling to upstream allocator

3. Error Handling

// PMR allocators can return nullptr!

std::pmr::vector<Data> vec{&limited_resource};

try {

vec.push_back(data);

} catch (const std::bad_alloc&) {

// Buffer exhausted

log_error("Memory exhausted");

// Graceful degradation

}

// Or check capacity proactively

if (vec.capacity() < vec.size() + 1) {

// Handle before allocation fails

}

4. Combining Resources

// Hierarchy: fast path → slow path → error

char fast_buffer[1024];

std::pmr::monotonic_buffer_resource fast{fast_buffer, sizeof(fast_buffer)};

char slow_buffer[16384];

std::pmr::monotonic_buffer_resource slow{slow_buffer, sizeof(slow_buffer), &fast};

std::pmr::vector<Packet> packets{&slow};

// Uses fast buffer first, overflows to slow, then fails

5. Move from std to pmr Gradually

// Phase 1: Identify hot paths with profiling

// Phase 2: Replace one container at a time

// Phase 3: Measure improvement

// Before

void process_messages(std::vector<Message>& messages) {

for (auto& msg : messages) {

std::string payload = decode(msg); // Hidden allocation

handle(payload);

}

}

// After (step 1: function-local)

void process_messages(std::vector<Message>& messages) {

char buffer[4096];

std::pmr::monotonic_buffer_resource mbr{buffer, sizeof(buffer)};

for (auto& msg : messages) {

std::pmr::string payload{&mbr};

decode(msg, payload); // Reuse buffer

handle(payload);

}

}

// After (step 2: propagate PMR through API)

void process_messages(std::pmr::vector<Message>& messages) {

// Caller controls memory resource

}

6. Testing Strategy

// Create memory pressure in tests

class LimitedResource : public std::pmr::memory_resource {

size_t limit_;

size_t used_ = 0;

protected:

void* do_allocate(size_t n, size_t a) override {

if (used_ + n > limit_) {

throw std::bad_alloc();

}

used_ += n;

return upstream_->allocate(n, a);

}

// ...

};

TEST(SensorProcessor, HandlesMemoryExhaustion) {

LimitedResource limited{1024}; // Only 1KB available

std::pmr::vector<Sample> samples{&limited};

// Verify graceful degradation

EXPECT_NO_CRASH(fill_samples(samples, 10000));

}

Surprising Findings from Real Benchmarks

After running comprehensive benchmarks, the results were different from expectations:

What I Expected vs. What I Found

| Expectation | Reality |

|---|---|

| PMR would be faster | PMR is 3-4x slower for simple operations |

| PMR would reduce variance significantly | Mixed results: Great for strings (3x better), worse for vectors |

| Pool allocator would be fastest | std::allocator is fastest for basic operations |

| PMR always wins on determinism | Not always: Map operations showed minimal improvement |

The Real Trade-off

PMR is NOT a performance win in all cases. The actual benefit is:

- When you need: Predictable timing, no heap usage, bounded worst-case

- What you sacrifice: 3-4x slower execution for basic operations

- Best use case: Real-time systems where 68µs±5.6% beats 16µs±10%

Benchmark Highlights

Vector operations (1000 push_back):

- std: 16.90µs (fast, 10% variance)

- pmr_pool: 68.86µs (slow, 5.6% variance) ← Best determinism

- Winner: Depends on your constraint (speed vs. predictability)

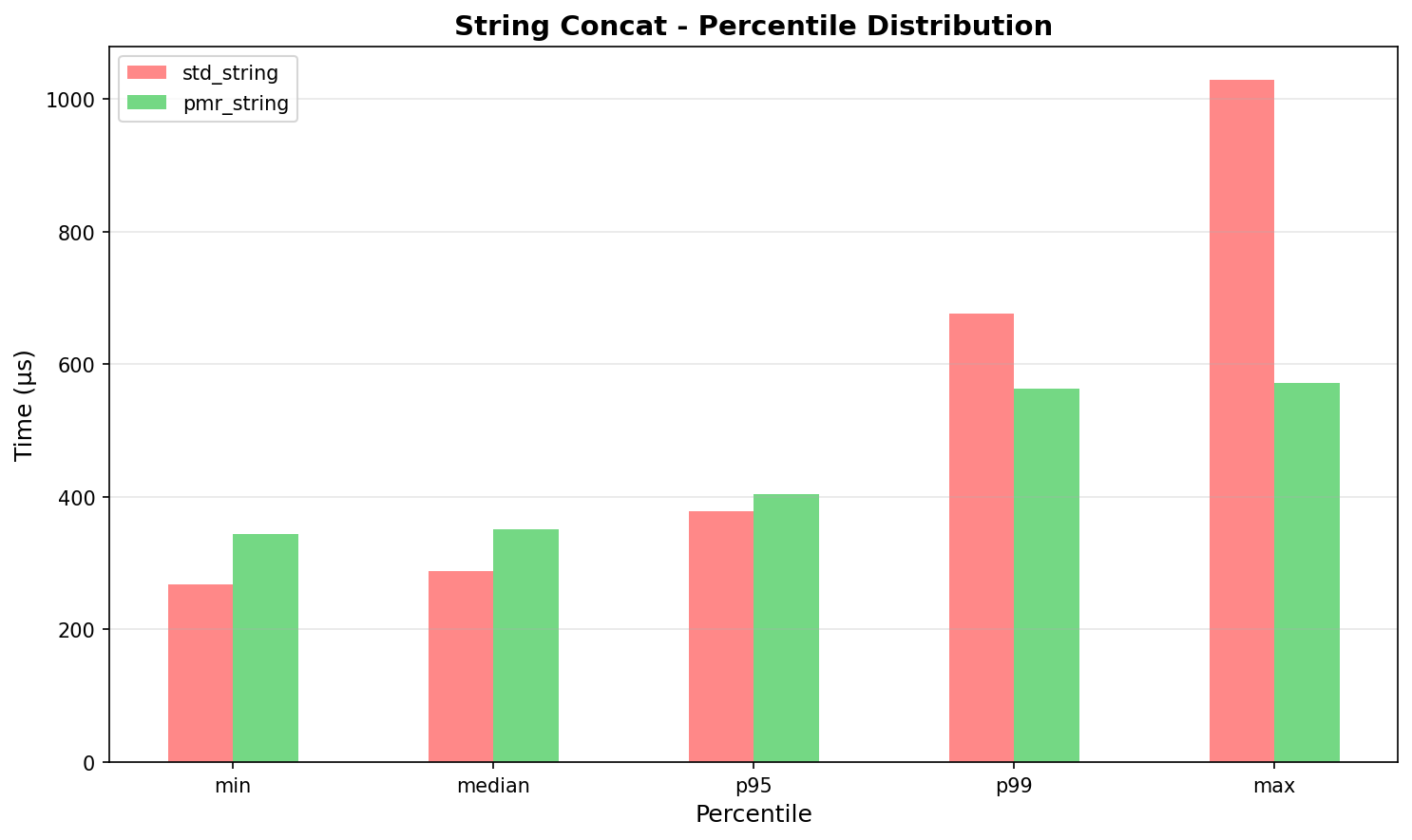

String concatenation:

- std: 307.77µs (CV: 29.52%)

- pmr: 360.17µs (CV: 9.40%) ← 3x more consistent

- Winner: PMR if you need determinism

Figure: String concatenation P95/P99 - PMR shows tighter distribution

Figure: String concatenation P95/P99 - PMR shows tighter distribution

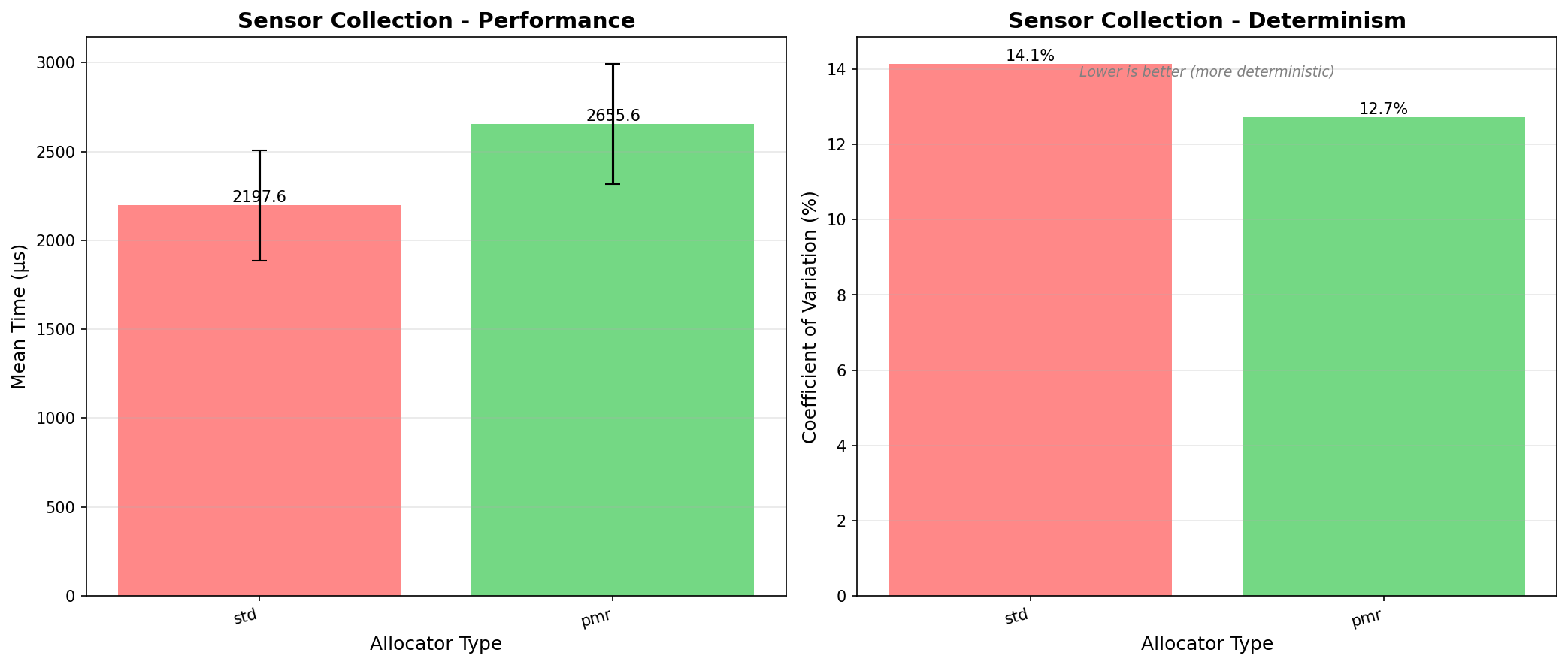

Sensor data collection (realistic embedded workload):

- std: 2197.62µs (CV: 14.15%)

- pmr: 2655.63µs (CV: 12.72%) ← Slight improvement

- Winner: Depends on whether 20% speed loss is acceptable for 10% better determinism

Figure 8: Sensor data collection - PMR trades 20% speed for slightly better consistency

Figure 8: Sensor data collection - PMR trades 20% speed for slightly better consistency

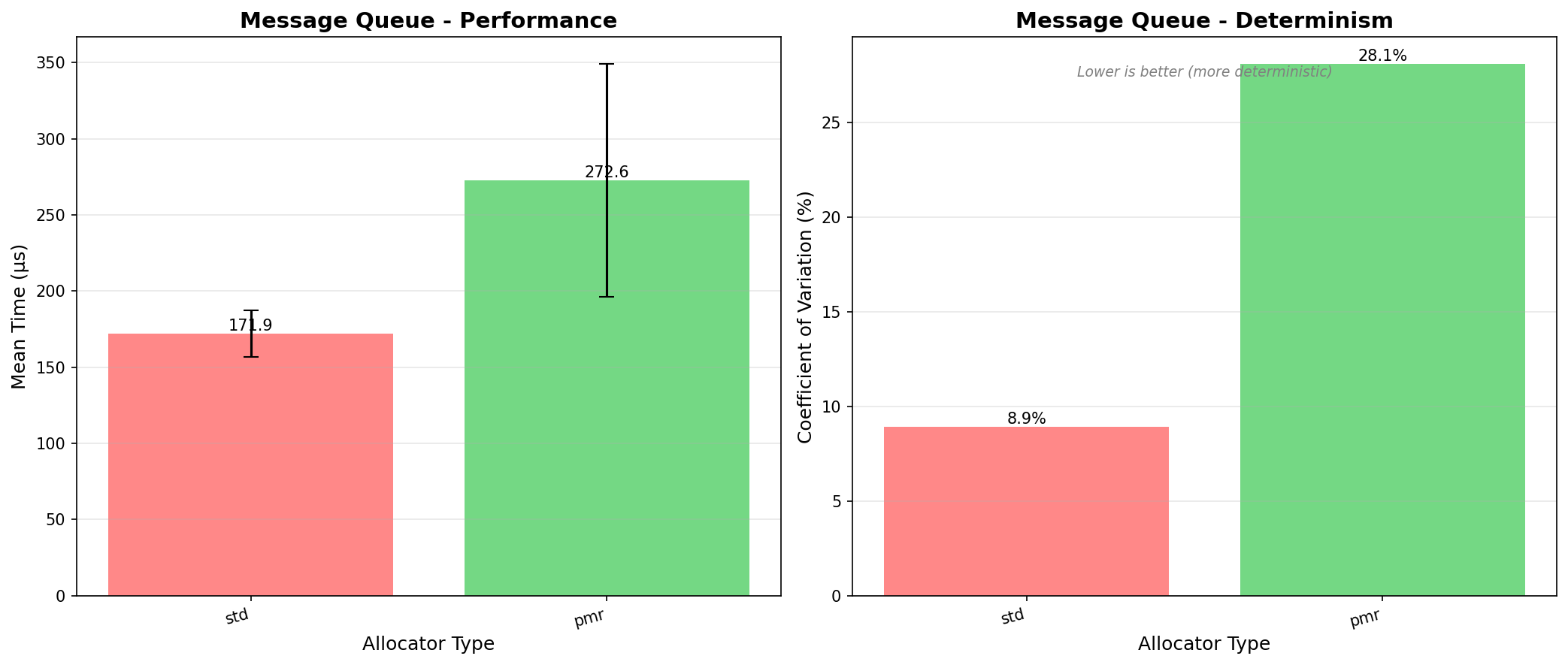

Message queue (mixed workload):

- std: 171.90µs (CV: 8.93%)

- pmr: 272.57µs (CV: 28.10%) ← Worse!

- Winner: std (better on both metrics)

Figure 7: Message queue benchmark - std::allocator wins on both speed AND consistency

Figure 7: Message queue benchmark - std::allocator wins on both speed AND consistency

PMR isn’t universally better. It trades raw speed for predictability. Profile your specific workload before switching.

Conclusions

Key Takeaways

✅ PMR offers predictability, not speed: Expect 3-4x slower but more consistent timing

✅ Use PMR for determinism: When low variance (68µs±5%) matters more than speed (16µs±10%) in real-time systems

✅ std::allocator is still fast: For non-critical paths, standard containers perform well

✅ Not a silver bullet: Profile first, PMR helps specific cases (strings, bounded allocations)

When to Use PMR

✅ Use PMR when:

- Hard real-time systems where consistent timing matters more than average speed (predictability over performance)

- Embedded systems where heap allocation must be avoided

- Safety-critical software requiring deterministic behavior

- Short-lived operations with known memory bounds

✅ Use std::allocator when:

- Raw performance is the priority (3-4x faster for basic ops)

- Workload has low natural variance (like our message queue example)

- Long-lived containers with unpredictable growth

- Development speed matters more than optimization

⚠️ Benchmark first:

- Results vary by workload (vector vs. string vs. map)

- Your hardware/compiler may show different ratios

- Profile to see if determinism improvement justifies speed loss

The Mental Model Shift

graph LR

A[Traditional:<br/>'Container owns memory'] --> B[PMR:<br/>'Container borrows memory']

B --> C[You control:<br/>• Where<br/>• When<br/>• How much]

C --> D[Better:<br/>• Determinism<br/>• Performance<br/>• Control]

style A fill:#ffe066,stroke:#f08c00

style B fill:#74c0fc,stroke:#1971c2

style D fill:#51cf66,stroke:#2f9e44

PMR isn’t about replacing std containers—it’s about giving you control when you need it. In embedded systems, that control often means the difference between “works most of the time” and “proven reliable.”

Quick Decision Matrix

| Your Situation | Recommendation | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Need minimum latency variance | pmr::pool_resource | CV as low as 5.6% |

| Need maximum raw speed | std::allocator | 3-4x faster for vectors |

| String-heavy workload | pmr::string | 3x better determinism |

| Mixed container operations | Profile first | Results vary (std won our message queue test) |

| Embedded, hard real-time | pmr::monotonic_buffer | Zero heap, bounded timing |

| General-purpose application | Stick with std:: | Faster and simpler |

References

- C++17 Standard: Memory Resources

- P0220R1: Adopt Library Fundamentals V1 TS Components for C++17

- Pablo Halpern: “Allocators@C++Now 2017”

- Bjarne Stroustrup: “A Tour of C++” (2nd Edition), Section 13.6

- MISRA C++:2023 Guidelines - Rule 18-4-1: Dynamic heap memory allocation shall not be used

- JSF AV C++ Coding Standards - AV Rule 206: Dynamic memory allocation shall not be used

- Embedded Artistry: “Practical Guide to Bare Metal C++”

- ARM Cortex-M7 Technical Reference Manual - Memory system performance characteristics

- A. Mahmutbegović, C++ in Embedded Systems: A practical transition from C to modern C++, Packt Publishing, 2024.